- Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Permits

- Boundary Waters Canoe Area Map

- Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Map

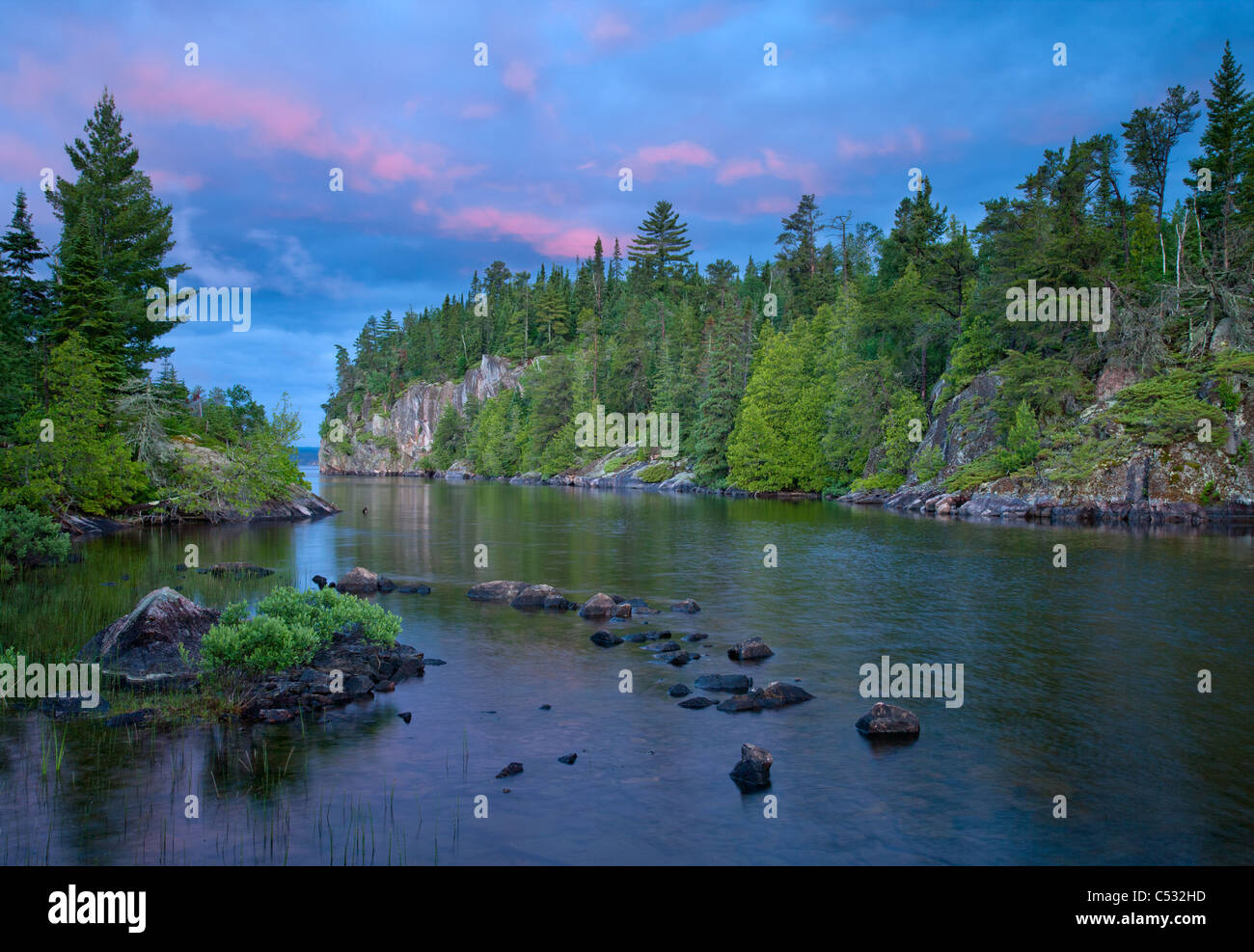

A Boundary Waters Outfitters canoe trip awaits you here in Ely Minnesota's Northwoods, start planning your adventure today! Boundary Waters Outfitters is located 7 miles outside Ely, Minnesota on the edge of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area - BWCA and situated on a pristine wilderness lake within the midst of a towering birch and pine forest.

The new European data protection law requires us to inform you of the following before you use our website:We use cookies and other technologies to customize your experience, perform analytics and deliver personalized advertising on our sites, apps and newsletters and across the Internet based on your interests. By clicking “I agree” below, you consent to the use by us and our third-party partners of cookies and data gathered from your use of our platforms. See our and to learn more about the use of data and your rights. You also agree to our.

Location/ / counties, United StatesNearest cityCoordinates:Area1,090,000 acres (4,400 km 2)Established1978Visitors105,000 (in 2015)Governing bodyThe Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness ( BWCAW or BWCA), is a 1,090,000-acre (4,400 km 2) within the in northeastern part of the US state of under the administration of the. A mixture of forests, glacial lakes, and streams, the BWCAW's preservation as a primitive wilderness began in the 1900s and culminated in the of 1978. It is a popular destination for both, hiking, and fishing, and is one of the most visited wildernesses in the United States.: 10.

The BWCAW within theThe BWCAW extends along 150 miles (240 km) the U.S.–Canada border in the of Minnesota. The combined region of the BWCAW, Superior National Forest, and and make up a large area of contiguous wilderness lakes and forests called the 'Quetico-Superior country', or simply the. Lies to the south and east of the Boundary Waters.: 1–3190,000 acres (770 km 2), nearly 20% of the BWCAW's total area is water. Within the borders of the area are over 1,100 lakes and hundreds of miles of rivers and streams. Much of the other 80% of the area is forest. The BWCAW is the largest remaining area of uncut forest in the eastern portion of the United States.The between the and runs northeast–southwest through the east side of the BWCAW, following the crest of the and.: 9 The crossing of the divide at was an occasion for ceremony and initiation rites for the of the 18th and early 19th centuries. The wilderness also includes the highest peak in Minnesota, (2,301 feet (701 m)), part of the.Located around the perimeter of the BWCAW are six ranger stations: in,.

Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Permits

The two nearby communities with most visitor services are Ely and Grand Marais. Several historic roads such as the, Echo Trail (County Road 116) and Fernberg Road (County Road 18) allow access to many wilderness entry points. Natural history. Main article:The lakes of the BWCAW are located in depressions formed by differential erosion of the tilted layers of the. For the past, massive have repeatedly the landscape.

The ended with the retreat of the from the Boundary Waters about 17,000 years ago. The resulting depressions in the landscape later filled with water; becoming the lakes of today.Many varieties of bedrock are exposed including:, as well as derived from. Greenstone of the located near Ely, Minnesota, is up to 2.7 billion years old. Of the comprise the bedrock of the eastern Boundary Waters. Ancient have been found in the of the. Forest ecology The Boundary Waters area is within the (commonly called the 'North Woods'), a transitional zone between the to the north and the to the south that contains characteristics of each. Trees found within the wilderness area include such as, and, as well as,.

And can be found in cleared areas. The BWCAW is estimated to contain 455,000 acres (1,840 km 2) of, woods that may have burned but have never been logged. Before fire suppression efforts began during the 20th century, were a natural part of the Boundary Waters ecosystem, with recurrence intervals of 30 to 300 years in most areas.On July 4, 1999, a powerful wind storm, or, swept across Minnesota, central Ontario, and southern Quebec. Winds as high as 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) knocked down millions of trees, affecting about 370,000 acres (1,500 km 2) within the BWCAW and injuring 60 people.

This event became known officially as the, commonly referred to as 'the Boundary Waters blowdown'. Although and portages were quickly cleared after the storm, an increased risk of wildfire due to the large number of downed trees became a concern. Forest Service undertook a schedule of to reduce the forest fuel load in the event of a wildfire. Smoke from the 2011The first major wildfire within the blowdown area occurred in August 2005, burning 1,335 acres (5.40 km 2) between Alpine Lake and Seagull Lake in the northeastern BWCAW.

In 2006, two fires at Cavity Lake and Turtle Lake burned more than 30,000 acres (120 km 2). In May 2007, the started near the location of the Cavity Lake fire, eventually covering 76,000 acres (310 km 2) in Minnesota and Ontario and becoming the most extensive wildfire in Minnesota in 90 years. In 2011, the ultimately grew to over 92,000 acres (370 km 2), spreading beyond the wilderness boundary to threaten homes and businesses. Smoke from the Pagami Creek Fire drifted east and south as far as the, Poland, Ukraine, and Russia. Common loonAnimals found in the BWCAW include,. It is within the range of the largest population of wolves in the, as well as an unknown number of.

It has also been identified by the as a globally important bird habitat.once inhabited the region but have disappeared due to predation by wolves, encroachment by deer, and the effects of a carried by deer which is harmful to both caribou and moose populations. Very rare sightings have been reported in nearby areas.

Human history Native Americans. Pictographs at Hegman Lake, as they looked in 2003Within the BWCAW are hundreds of prehistoric and on rock ledges and cliffs. The BWCAW is part of the historic homeland of the people, who traveled the waterways in made of. Prior to Ojibwe settlement, the area was sparsely populated by the, who migrated westward following the arrival of the Ojibwe. It is thought that the located on a large overlooking rock wall on North Hegman Lake were most likely created by the Ojibwe. The pictograph appears to represent Ojibwe meridian constellations visible in winter during the early evening, knowledge of which may have been useful for navigating in the deep woods during the winter hunting season.

The, just east of the BWCAW at the community of, is home to a number of Ojibwe to this day. European exploration and development. A canoe during the fur trade eraIn 1688 the explorer became the first European known to have traveled through the BWCAW area. Later, during the 1730s, and others opened the region to trade, mainly in beaver pelts. By the end of the 18th century, the had been organized into groups of canoe-paddling working for the competing and Companies, with a North West Company fort located at the on Lake Superior. The final was held at Grand Portage in 1803, after which the North West Company moved its operations further north to Fort William (now ). In 1821 the North West Company merged with the Hudson's Bay Company and the center of the fur trade moved even further north to the posts around Hudson Bay.: 5–8During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the area's legal and political status was disputed.

The, which ended the in 1783, had defined the northern border between the United States and Canada based on the inaccurate. Ownership of the area between and Lake Superior was unclear, with the United States claiming the border was further north at the and Canada claiming it was further south beginning at the. In 1842, the clarified the border between the United States and Canada using the old trading route running along the and (today the BWCAW's northern border).: 8–9The BWCAW area remained largely undeveloped until gold, silver and iron were found in the surrounding area during the 1870s, 1880s and 1890s. Logging in the area began around the same time to supply lumber to support the mining industries, with production peaking in the late 1910s and gradually trailing off during the 1920s and 1930s.: 9–12.Protection In 1902, Minnesota's Forest Commissioner persuaded the state to reserve 500,000 acres (2,000 km 2) of land near the BWCAW from being sold to loggers. In 1905 he visited the area on a canoe trip and was impressed by the area's natural beauty. He was able to save another 141,000 acres (570 km 2) from being sold for development.

He soon reached out to the Ontario government to encourage them to preserve some of the area's land on their side of the border, noting that the area could be 'an international forest reserve and park of very great beauty and interest'. This collaboration led to the creation of the Superior National Forest and the Quetico Provincial Park in 1909.: 15–16The BWCAW itself was formed gradually through a series of actions. By the early 1920s, roads had begun to be built through the Superior National Forest to promote public access to the area for recreation. In 1926 a section of 640,000 acres (2,600 km 2) within the Superior National Forest was set aside as a roadless wilderness area by Secretary of Agriculture. This area became the nucleus of the BWCAW.

In 1930, Congress passed the Shipstead-Newton-Nolan Act, which prohibited logging and dams within the area to preserve its natural water levels. Through additional land purchases and shifts in boundaries, the amount of protected land owned by the government in the area grew even further. In 1938, the area's borders were expanded and altered (roughly matching those of the present day BWCAW), and it was renamed the Superior Roadless Primitive Area.Additional laws focused on protecting the area's rustic and undeveloped character.

In 1948, the Thye-Blatnik Bill authorized the government to purchase the few remaining privately owned homes and resorts within the area. In 1949, President signed Executive Order 10092 which prohibited aircraft from flying over the area below 4,000 feet. The area was officially named the Boundary Waters Canoe Area in 1958. The of 1964 organized it as a unit of the. The 1978 established the Boundary Waters regulations much as they are today, with limitations on and, a permit-based quota system for recreational access, and restrictions on logging and mining within the area. That same year the Forest Service began referring to it as 'BWCAW' to recognize its wilderness character.

Land use disputes Some aspects of the BWCAW's management and conservation have been controversial. 1971 A rule limiting visitors to 'designated campsites' on heavy-use routes is instituted by the U.S. Forest Service.

Cans and glass bottles are prohibited from the Boundary Waters. According to the U.S. Forest Service, the measure is expected to reduce refuse by 360,000 pounds (160 t), saving $90,000 per year on cleanup.1975 October, Eighth District Representative (D-MN) introduces a bill that if passed would have established a Boundary Waters Wilderness Area of 625,000 acres (253,000 ha) and a Boundary Waters National Recreation Area (NRA) of 527,000 acres (213,000 ha), permitting logging and mechanized travel in the latter area and removing from wilderness designation a number of large scenic lakes such as La Croix, Basswood, Saganaga, and Seagull. The bill is strongly opposed by environmentalists.1978 October 21, Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act, U.S.

Public Law 95-495, is signed. The act adds 50,000 acres (20,000 ha) to the Boundary Waters, which now encompasses 1,098,057 acres (444,368 ha), and extends greater wilderness protection to the area. The name is changed from the Boundary Waters Canoe Area to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. The Act bans logging, mineral prospecting, and mining; all but bans snowmobile use; two snowmobile routes remain to access Canada; limits motorboat use to about two dozen lakes; limits the size of motors; and regulates the number of motorboats and long established motorized. It calls for limiting the number of motorized lakes to 16 in 1984, and 14 in 1999, totaling about 24% of the area’s water acreage.1989 Truck portage testing. According to the 1978 BWCAW Act: Nothing in this Act shall be deemed to require the termination of the existing operation of motor vehicles to assist in the transport of boats across the portages from Sucker Lake to Basswood Lake, from Fall Lake to Basswood Lake, and from Lake Vermilion to Trout Lake, during the period ending January 1, 1984.

Following said date, unless the Secretary determines that there is no feasible non-motorized means of transporting boats across the portages to reach the lakes previously served by the portages listed above, he shall terminate all such motorized use of each portage listed above.1989 – U S Forest Service with the University of MN conduct feasibility tests on the three truck portages. It is determined that trucks should remain.1990 – Friends of the Boundary Waters, Sierra Club and six other environmental groups sue to have trucks removed; CWCS joins the U S Forest Service as intervenors.1992 – Appeals court sides with U S Forest Service that trucks should remain. Friends of the Boundary Waters and coalition appeal to. A fire area typical at wilderness campsites throughout the BWCAWThe BWCAW attracts approximately 250,000 visitors per year, making it one of the most visited wilderness areas in the United States.: 10 It contains more than 2,000 backcountry campsites, 1,200 miles (1,900 km) of canoe routes, and 12 different hiking trails and is popular for, fishing, and enjoying the area's remote wilderness character.Permits are required for all overnight visits to the BWCAW. Quota permits are required for groups taking an overnight paddle, motor, or hiking trip, or a motorized day-use trip into the BWCAW from May 1 through September 30. These permits must be reserved in advance. Day use paddle and hiking permits do not require advance reservation and can be filled out at BWCAW entry points.

From October 1 through April 30, permit reservations are not necessary, but a permit must be filled out at the permit stations located at each entry point. Each permit must specify the trip leader, the specific entry point and the day of entry. The permits are for an indefinite length, although visitors are only allowed one entry into the wilderness and cannot stay in one campsite for more than 14 nights. Canoeing. Junction of the Eagle Mountain and Brule Lake TrailsFishing is a popular activity in the BWCAW. Game species include, and,.

Trout including, and are also found. Limited stocking of walleye, brown trout and lake trout is done on some lakes. Hiking The BWCAW contains a variety of hiking trails. Shorter hikes include the trail to (7 miles (11 km)). Loop trails include the, the, and the. The and are the two longest trails running through the BWCAW. The Border Route Trail runs east-west for over 65 miles (105 km) through the eastern BWCAW, beginning at the northern end of the and following ridges and cliffs west until it connects with the.

Boundary Waters Canoe Area Map

The Kekekabic Trail continues for another 41 miles (66 km), beginning near the Gunflint Trail and passing through the center of the BWCAW before exiting it near Snowbank Lake. Both the Border Route and the Kekekabic Trail are part of the longer.

Notable people associated with the BWCAW., is recognized today as a leading advocate for the preservation of the Quetico-Superior lake area and what would become the BWCA., Minnesota author and, wrote extensively about the Boundary Waters and worked to ensure preservation of the wilderness., known as the 'Rootbeer Lady', lived in the BWCAW for 56 years (alone after 1948) until her death in 1986, and was the last resident of the BWCA.References. Forest Service. Retrieved 28 August 2006.

^ (pdf). USDA – Forest Service. ^ Searle, R.

Newell (1977). Saving Quetico-Superior, A Land Set Apart. Minnesota Historical Society Press. ^ Churchill, James (2003). Paddling the Boundary Waters and Voyageurs National Park.

Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Map

Globe Pequot. Podruchny, Carolyn (June 2002).

Canadian Historical Review. University of Toronto Press, Journals Division.

83 (2): 165–95. (Abstract). ^ Ojakangas, Richard; Matsch, Charles (1982).

'Minnesota's Geology'. Minneapolis:. ^ Heinselman, Miron (1996).

The Boundary Waters Wilderness Ecosystem. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. Weiblen, Paul W. The Conservation Volunteer. Barghoorn, Elso S.; Tyler, Stanley A. 'Microorganisms from the Gunflint Chert'. 147 (3658): 563–577.

Heinselman (1996), p. 18, Table 4.1. This figure is for solid contiguous areas of virgin forest; it does not include some smaller areas within cut-over forests, nor some shoreline areas of virgin woods. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Friends of the Boundary Waters Wilderness. Archived from on 2015-01-22.

Etten, Douglas (2011-09-13). Lakeland Times. Gabbert, Bill. Wildfire Today. Retrieved 2011-09-13. Retrieved 2011-09-13. USDA – Forest Service.

Mech, L. David; Nelson, Michael E.; Drabik, Harry F. 'Reoccurrence of Caribou in Minnesota'. The American Midland Naturalist. 101 (8): 206–208. Furtman, Michael (2000).

Magic on the Rocks: Canoe Country Pictographs. Duluth, Minn.: Birch Portage Press. Morse, Eric W. Ottawa, Canada: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. Lass, William E.

Minnesota's Boundary with Canada, pp. Minnesota Historical Society,.

^. United States Department of Agriculture – Forest Service. ^ Wilbers, Stephen. Retrieved 27 September 2009., Superior National Forest, United States Forest Service. Kelleher, Bob.

Minnesota Public Radio. Furst, Randy (14 February 2015).

Minneapolis Star-Tribune. Hemphill, Stephanie. Minnesota Public Radio.

Kraker, Dan, Minnesota Public Radio, September 7, 2018. Dvorak, Robert G.; Watson, Alan E.; Christensen, Neal; Borrie, William T.; Schwaller, Ann. United States Department of Agriculture – Forest Service. P. 11. Pauly, Daniel (2005). Exploring the Boundary Waters. University of Minnesota Press.

Beymer, Robert; Dzierzak, Louis (2009). Boundary Waters Canoe Area: Western Region.

Wilderness Press. Beymer, Robert; Dzierzak, Louis (2009). Boundary Waters Canoe Area: Eastern Region. Wilderness Press. North Country Trail Association. North Country Trail Association.External links Wikimedia Commons has media related to.Further reading. Fox, Porter,., October 21, 2016, p. 1.

Proescholdt, Kevin; Rapson, Rip: and Heinselman, Miron L. Troubled Waters.

North Star Press of St.